The construction of New Holland was intricately tied to the history of the Admiralty. As part of his efforts to build Saint Petersburg up from swampland, Peter the Great brought in Dutch shipbuilders, giving them a workspace along the left bank of the Neva. This area soon began to resemble more of a foreign port, giving way to the nickname “Holland,” which was later fixed to the man-made island formed by the Moika river and the Admiralteysky and Kryukov Canals.

In the 1730s, when the island itself was at last complete, it was handed over to the navy, who commissioned the architect Korobov to design wooden barracks to store the lumber for ship-building.

In the middle of the 18th century, these wooden barns were replaced by sturdier stone structures. The architect Savva Chevakinsky formulated an innovative way to store planks vertically, further defining the borders of the island with his austere, fortress-like constructions. The facades themselves were left to a different architect – Jean-Baptiste Vallin de la Mothe, who specialized in the type of classical flourishes exemplified in the gateway to the island. The proposals of these two architects were combined and then handed over to the engineer Johann Gerhard for their realization. The final construction of the project would be completed only at the end of the 18th century.

The Building of New Holland

The history of New Holland begins at the very moment when Peter the Great first set about building St Petersburg. Parallel to the city’s founding was the formation of a Northern fleet. In 1704, the headquarters of the Admiralty were relegated to the left bank of the Neva River. In order to facilitate shipbuilding and the delivery of materials including lumber, the Admiralty ordered a series of canals, which is how the Admiralteysky and Kryukov Canals came to connect the Neva and Moika rivers.

Even in the process of its construction, the area around the Admiralty had been colloquially referred to as “New Holland” – a nickname it owed to the distinctly Dutch look of its barracks. Other accounts attribute the name to the presence of Dutch builders, whom Peter the Great had brought in to help build his ideal, “European” city. These visiting specialists filled the area not only with foreign tongue, but also with the delicately arched bridges one might have found along canals in Amsterdam.

While still under the reign of Peter the Great, the territory of the future New Holland already boasted a pond, whose form seems more suited to courtly leisure than to function. Many researchers believe that Peter the Great may have originally kept a small palace for himself alongside it (a hypothesis reinforced by documentary evidence, including selected early maps of St Petersburg).

The First Structures

From 1732 on, New Holland was administered under the authority of the Navy, who promptly decided to extend the Admiralteysky Canal and erect a series of barracks to store the lumber for shipbuilding. The construction was carried out by architect Ivan Kuzmin Korobov. By 1738, the island boasted eight lumber barns.

The travelogues of Karl Rheingold Burke provide a glimpse of how the island may have looked in the 1730s: “Across the canals, lined with the aforementioned ropes and hoisting gear, lies New Holland, that is, the set of barracks for the oak lumber for shipbuilding – which is stored in small pieces as well as in large planks and boards. These barracks are wooden, but all of the walls are grated, allowing air circulation throughout the space and keeping the wood dry. In winter and in humid weather, all these openings can be shut, sealing out extra moisture.”

At the beginning of the 1750s, the wooden barns of New Holland were in serious decay, and the Admiralty Board decided it was time to bring stone to the island, which would also improve the air circulation in the lumber storage. At that time, the post of chief architect of the Admiralty had been handed down from Korobov to his former apprentice, Savva Chevakinsky. From 1753, Chevakinsky supervised the first reconstruction of New Holland, which had been planned by Korobov but was yet to be realized due to a lack of funds. This reconstruction lasted ten years.

On October 27, 1763, the Admiralty Board commissioned Chevakinsky to draft a general plan for New Holland, including barracks “with the same layout and the same sort of storage facilities, only on stone pillars, with ramps for easy loading.”

On November 13, 1763, he presented the board with blueprints following the Admiralty’s instructions to the letter and pre-approved by the Commission for Stone Builders in St Petersburg and Moscow. As an additional touch, he made sure his plan added to the city around it, transforming what could have been mundane, functional buildings into striking architectural ensembles. As another departure, he had designed three barns, the same width but at varying height, which together could hold enough lumber for 15 ships. This second plan, however, was never realized. In 1765, the architect returned to the board with a new proposal that laid out the system of vertical storage instead.

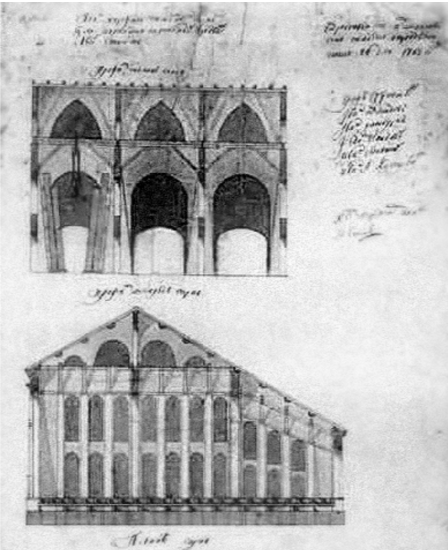

Savva Chevakinsky’s Plan

The esteemed architect’s new plan proposed a system of 63 “cones,” as he called the silos, which were shaped like truncated triangles. The interiors of each column were reinforced by counterweights, which enabled the system of wooden grids upon which lumber was stored. The central parts of the buildings along the Moika River and the Kryukov Canal were outfitted to sort the lumber by the length of the planks, which were then stored according to their size. The barns, planned as stone galleries with arches, had been designed to facilitate delivery from land or from water. The interior courtyard was equipped as a space for the cutting of lumber, unloading of barges and the set-up of smaller courts.

Chevakinsky’s innovative proposal was approved with a few modifications; the Admiralty Board decided that: “The large barns intended to stand along the Kryukov Canal should instead line the Moika and run along the Kryukov Canal, in the aesthetic interest of the city.” These changes were never undertaken, as the reworking of New Holland’s facades introduced yet another new architect into the project – court favorite Jean Baptiste Vallin de la Mothe.

The Facades of Vallin de la Mothe

When designing the facades for the warehouses, Vallin de la Mothe underlined the austerity of the surroundings using the principles of an arcade: he accented the gates in the center of the arches and added Greek columns to the rounded corner barns, striking an aesthetic unity among the ensemble of buildings. Vallin de la Mothe is to thank for the marvelous gateway, embodying the height of Classicism and quickly becoming the symbol for the island.

On July 15, 1765, Vallin de la Mothe’s proposal for the facades was officially approved. However, on the path to realizing these plans, Chevakinsky and Vallin de la Mothe encountered a considerable obstacle: since exact measurements of the island along the Moika River had been impossible to produce, both plans had been drawn up using estimations. Vallin de la Mothe’s arch was actually a different width than the canal it was to stand over, and Chevakinsky’s complex had a more acute corner than the territory of the island would allow. What’s more, there were plenty of moments when the two plans proved impossible to combine. Later, Chevakinsky would try to correct one such mistake: the inaccurate measurement of the piles under the Admiralteysky Canal. This mistake led to his prompt dismissal and the engineer Johann Gerard stepped in as the new architect of New Holland.

Johann Gerard Steps In

Even now, one hears the anecdote of how Gerard claims to have “lost” Vallin de la Mothe’s blueprints and ventured his own version of the island instead. Alas, the Admiralty Board was able to produce a copy of the earlier plans, corrected by Chevakinsky himself, and Gerard was obliged to carry out the construction as planned. He did manage to slip in a limited revisal of some aspects, eliminating many of the constructive corrections. In the summer of 1767, his version of the proposal was approved.

In order to house all of the bounty from the imperial Intendant’s successful expedition, from the 1765-70s, over thirty cones were built along the Moika, and twenty more along the Kryukov Canal. These facilities entered into operation from 1773 on, although their construction was not complete until 1779 (or even 1784, by some accounts.) The structures were erected at a backbreaking tempo; at one point over 500 men were working on the island. The process of raising the gates was a particularly demanding endeavor. The columns were fashioned from granite blocks, each of which weighed around four tons; in order to prepare the cement foundations for these columns, “the master of machines” Kuzma Petrov had to bring in a special mill for added power. The construction of the arch alone stretched over seven years, coming to an end only in 1777. However, in 1782, the gateway already needed reconstruction and a re-working of the embankments, which was only finished in 1784.

Gerard’s plan would never be completed in its entirety; the wars in Turkey and Sweden (1788-1789) interfered. Construction remained unfinished within the interior of the water tank complex, plans for a second arch over the Kryukov Canal were abandoned, and even the walls of the complex that were standing never received their final coat. Regardless, the warehouse facilities were used quite actively, and the complex of buildings itself – designed by Vallin de la Mothe and engineered by Gerard and his apprentice Mikhail Vetoshnikov – was cited as one of the outstanding examples of early classicism in Russian architecture.

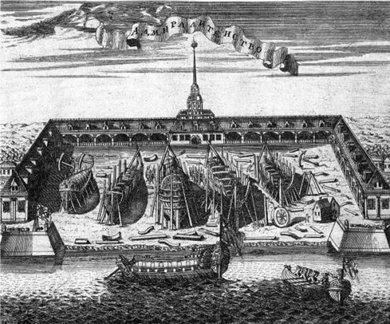

Engraving of the Admiralty

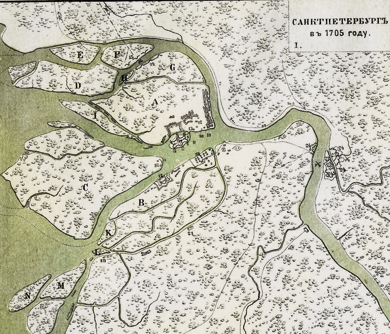

Engraving of the Admiralty Map of Saint Petersburg in 1705

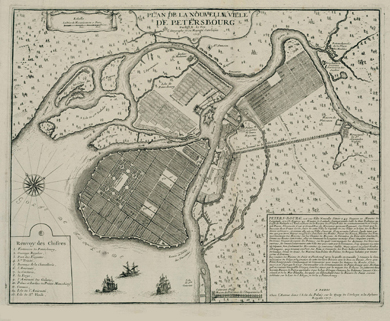

Map of Saint Petersburg in 1705  Map of Saint Petersburg in 1717

Map of Saint Petersburg in 1717  Savva Chevakinsky

Savva Chevakinsky  Architectural drawing by Savva Chevakinsky

Architectural drawing by Savva Chevakinsky